35% of the New Testament is comprised of letters.

Today, if you want to communicate with a friend, work colleague or government department, you can use one of many channels – you could

- pick up the phone and speak to them or text them;

- video message them, if you have an iPad or similar;

- email them or send a message via Facebook; or

- hand-write a letter (perish the thought!).

In the ancient world of the New Testament, the only option available was to write a letter. However, we mustn’t assume that letter writing 2,000 years ago was anything like writing a letter today.

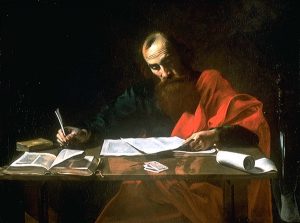

Saint Paul Writing His Epistles (1620) by Valentin de Boulogne. In public domain.

Consider this painting – the Apostle Paul is shown sitting at a desk with a quill in his hand and sheets of paper in front of him. In addition, there’s an open Bible on the table, ready to be consulted – no doubt it contains the New Testament – it’s certainly thick enough! And is that a deck of cards that I see on the table?

It is INACCURATE

Paper wasn’t invented in China until well after 100 A.D., by which time all of the New Testament had been written.

The painter has drawn from the way in which letters were written in his day to construct this portrait, but he has made some clear mistakes. Hence, the obvious first question to be asked is – how were the New Testament letters produced? A number of points need to be made:

- SCRIBES. The normal practice was for the author to dictate the letter’s contents to a scribe – a professional skilled in the use of the writing materials in use at that time (cf. Rom. 16:22 & 1Co 16:21);

- TIME CONSUMING and COSTLY. Have you ever tried to read right through one of the Epistles of Paul, such as 1 or 2 Corinthians? Imagine how long it would have taken to dictate it. The whole process was long and expensive;

- SITUATIONAL. Most New Testament letters were written to address specific problems or situations;

- COOPERATIVE EFFORT. 1st century letter writing was a social event. Scholars believe that the NT authors dictated many of their letters in the company of their trusted associates. No doubt they would have discussed the topics to be included in the letter in much the same way that eldership teams talk about problems today;

- FORM and STYLE.

When we write letters we make use of the forms of address and styles of letter writing (“templates” in other words) that are in common use today. The one shown here is a template for a formal, business letter; for a personal letter, we might omit the company address at the left side and use “Yours truly” at the end.

The Apostles who wrote (dictated) the letters we have in the New Testament used the letter forms that were common in their day. There are normally four or five segments [i]

The Apostles who wrote (dictated) the letters we have in the New Testament used the letter forms that were common in their day. There are normally four or five segments [i]

- 1st. Opening (sender and any co-senders, addressee[s], greeting);

- 2nd. Thanksgiving (often including an intercessory prayer and possibly a reference to the end-times and our hope in Christ);

- 3rd. Body of the letter (formal opening, background, followed by the reason for writing the letter and often some Theological explanations of the principles needed to address it);

- 4th. Paraenesis, i.e., exhortation and/or admonition, correction and disciplinary pronouncements;

- 5th. Closing (greetings, sometimes with the author’s own hand being added, doxology and benediction)

The 3rd and 4th segments are sometimes repeated, so that a letter might look like this: 1 – 2 – 3a – 4a – 3b – 4b – 3c – 4c – 5. Alternatively, especially in Paul’s letters, repetitions of segments 3 & 4 may be interwoven so that the boundaries between them are almost impossible to discern;

- POSTAL ARRANGEMENTS. There was no Postal Service in the 1st century. Instead the author would have to arrange for the letter to be sent with a traveller who was going in the right direction;

- TRANSMISSION of CONTENTS. The normal practice was for the letter to be read aloud at a church meeting;

- COMBINATION and EDITING. In some cases, such as Paul’s 2nd letter to the Corinthians, a number of smaller letters have been combined into one. There is also evidence that an editing process took place in some cases, though not to change the message in any way. Rather, as time went on, some older terms and references needed to be explained if they were to be understood by the current generation.

The second question to be asked is – who wrote all of these letters?

| Paul | John | Peter |

| 1 Thessalonians – 50-51 AD

2 Thessalonians – 52-53 Galatians – 53-55 1 Corinthians – 54 2 Corinthians – 55-56 Romans – 57-58 Philippians – 60-62 Colossians – 60-61 Philemon – 60-61 Ephesians – 60-61 1 Timothy – 60-62 Titus – 62-64 2 Timothy – 64-67 |

1 John – early 90s AD

2 John – early 90s AD 3 John – early 90s AD |

1 Peter – early 60s A.D.

2 Peter – 63-65 |

| James | Jude | ?? |

| James – 60s A.D. | Jude – 64-68 A.D. | Hebrews – 64-68 A.D. |

The above tables list the letters of the New Testament beneath the name of the person generally credited by evangelicals with writing the letter. The dates of writing, (shown thus – 55) are uncertain, but these are the best estimates as shown in the Zondervan Study Bible.

The final question that needs to be answered has to do with how we may best understand them in our modern context. I suggest the following strategy as a “starter for 10”[ii]:

- Read the entire letter in one sitting. Then continue doing so over a few days to allow it to “sink in”

- Reconstruct the historical context. (see full article)

- Identify the literary context. (see full article)

Read the text again – more carefully. Observe!!! Pray!!! Observe!!! Make notes!!! Pray!!! Apply!!!

To “dig deeper”, CLICK HERE to download the full article.

[i] See chapter 7 – “The Ancient Letter Genre” of An Introduction to the New Testament, (2nd Edition), by Charles B. Puskas and C. Michael Robbins, published by The Lutterworth Press in December 2013, ISBN: 9780718840877, pp 134-143. A pdf version can be found at http://www.lutterworth.com/pub/introduction%20to%20new%20testament%20ch7.pdf, accessed on 3 March 2017

[ii] Taken from Grasping God’s Word by J. Scott Duvall and J. Daniel Hays, published by Zondervan in May 2012, ISBN-13: 978-0310492573