Introduction:

As Christians living in the 21st Century, and familiar with the many and varied forms of communication that bombard us daily, we are all too familiar with the concept of the “sequel”. “Despicable Me” becomes “Despicable Me 2”, and then “Despicable Me 3” in quick succession, and almost as fast as the studios can churn them out. Fortunately, these particular sequels have proven to be at least as good as the original, but this has not always been the case. Who can forget “Ocean’s Twelve” the follow up to “Ocean’s Eleven”, and who has even heard of “Oliver’s Story” the sequel to “Love Story”?

The Book of Acts can be thought of as a sequel to the Gospel of Luke, first of all because it was written by the same author. In addition, a comparison of the Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts shows some remarkable similarities – especially in the ordering of events:

| Luk 1:3 NIV … I too decided to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, | Both books are addressed to “Theophilus” | Act 1:1 NIV In my former book, Theophilus, I wrote … |

| Luk 3:21-22 NIV … Jesus was baptized too. … (22) and the Holy Spirit descended on him in bodily form like a dove. | Close to the start of both books, the empowering anointing of the Holy Spirit is emphasized. | Act 2:4 NIV All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit enabled them. |

| Luk 4:18-19 NIV “The Spirit of the Lord is on me, because he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners and recovery of sight for the blind, to set the oppressed free, (19) to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.” |

Early in both books Luke shows how first Jesus and then His Apostles are fulfilling Old Testament prophecy. |

Act 2:17ff NIV “‘In the last days, God says, I will pour out my Spirit on all people. Your sons and daughters will prophesy, your young men will see visions, your old men will dream dreams. (18) Even on my servants, both men and women, I will pour out my Spirit in those days, and they will prophesy. |

| Luk 5:17-26 NIV One day Jesus was teaching, … And the power of the Lord was with Jesus to heal the sick. (18) … (24) So he said to the paralyzed man, “I tell you, get up, take your mat and go home.” | First miracle – healing of a man paralysed. | Act 3:1-10 NIV One day Peter and John were going up to the temple … (2) Now a man who was lame from birth was being carried to the temple gate … (4) Peter looked straight at him, as did John. … (6) Then Peter said, “… In the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, walk.” |

… and so we could go on …

Finally, the fact that Acts is a sequel is seen very clearly when the end of the Gospel is compared to the beginning of Acts:

- Luke ends with the resurrected Jesus telling His disciples to stay in Jerusalem until “you have been clothed with power from on high” (24:49). He then ascends into heaven (24:50ff).

- Acts begins by summarizing this ending (1:1-2), and by repeating Jesus’ command to wait in Jerusalem “for the gift my Father promised” (1:4). Then Luke retells Jesus’ ascension into heaven (Acts 1:4-11).

Acts is very definitely a sequel – a triumphant sequel – and a more than worthy continuation of the story of the advancement of God’s Kingdom that began in the Gospel of Luke. This sequel is no disappointment – if anything, the stories it relates take things to a whole new level of supernatural triumph in the face of seemingly insurmountable opposition. Acts describes one victory after another as Jesus’ followers (the Church) march unstoppably all over the Mediterranean world of the 1st century. Yes, there are setbacks, but nothing stands in the way for too long – Christ is triumphant in and through His faithful witnesses!

Title of the Book

We have come to know Luke’s sequel as the “Acts of the Apostles”, but this isn’t really a true reflection of its contents. The very earliest manuscripts (written in Greek of course) don’t give it a name at all; the title as we have it today was added later, probably in the late 2nd century, as a way of quickly identifying it from other books in the New Testament. Although it does describe the acts of some of the Apostles, notably Peter, John and Paul, other key players such as Barnabas, John-Mark, Stephen and Philip appear at certain points. It would be more accurate to refer to it as the “The Acts of God through His Spirit-Anointed People”, or perhaps “The Acts of the Holy Spirit in the Early Church”.

Structure

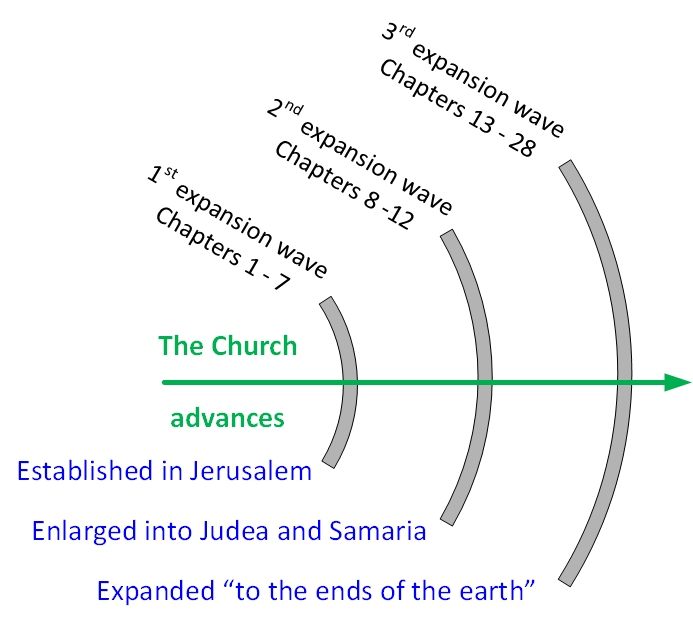

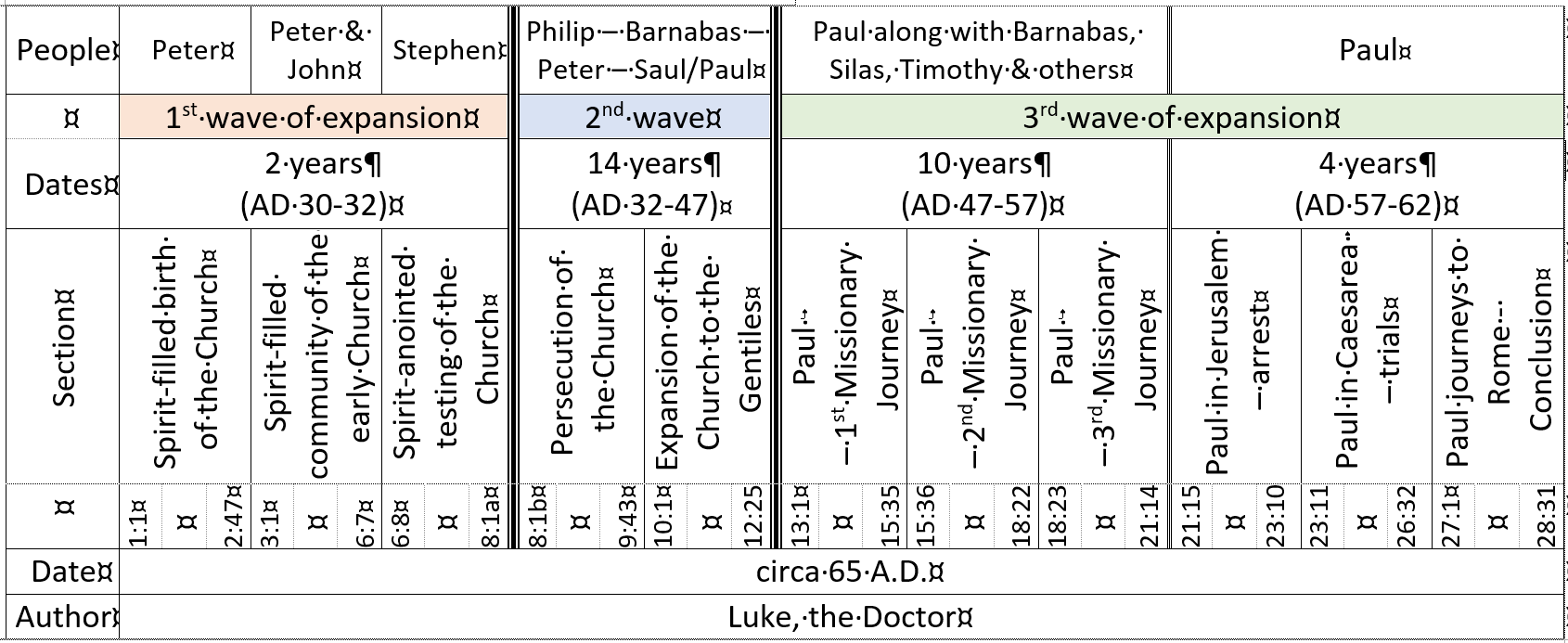

There have been a number of attempts to produce a structure for Acts, and the majority of scholars recognize that it divides into three overlapping sections as shown below.

It is useful to keep this three-part division in mind, as it makes the following, more detailed structure diagram easier to understand and engage with:

The Highlights – the Trailer

Imagine that you were the Director of a blockbuster film telling the story of Acts (not a bad idea actually …). What bits of the film would you put into the trailer? I suggest the following events might make the shortlist:

- The Day of Pentecost – baptism with Holy Spirit (2:1 – 13);

- Peter’s Sermon at Pentecost – 3,000 Jewish believers added (2:14 – 41);

- A lame beggar gets healed (3:1 – 10);

- Ananias and Sapphira – lying to the Holy Spirit (5:1 – 11);

- The Martyrdom of Stephen (6:1 – 7:60);

- The Ethiopian Eunuch and Philip (8:26 – 40);

- Saul’s Conversion on the road to Damascus (9:1 – 31);

- Peter’s vision of the unclean animals – he baptizes Cornelius, a Gentile (10:1 – 48);

- Peter’s miraculous escape from prison (12:6 – 19);

- 2nd lame man (in Lystra) gets healed – during Paul’s 1st missionary journey – Paul stoned (14:8 – 23);

- The Jerusalem Council recognizes Gentiles as equal believers (15:1 – 35);

- Paul’s vision of the Macedonian man – 2nd missionary journey (16:6 – 10);

- Paul and Silas in prison at Philippi – the conversion of the jailer & his family (16:16 – 40);

- Paul in Athens – the “unknown god” (17:16 – 34);

- Paul in Corinth (18:1 – 17);

- Paul in Ephesus – 3rd missionary journey – the riot of the silver smiths (19:1 – 41);

- Paul arrested in the Jerusalem temple (21:27 – 22:30);

- The plot of kill Paul – Romans take him to Caesarea (23:12 – 24:21);

- Paul sails for Rome – storm and shipwreck on Malta (27:1 – 28:10);

- Paul arrives in Rome (28:11 – 28:31)

OK – so maybe it’s a long list. Can you imagine the immense difficulty the director would have in choosing which scenes to include and which to leave out?

Themes

The book of Acts is chock full of dramatic incidents – all of which have been carefully chosen and compiled by Luke to demonstrate:

- The power of the Holy Spirit to transform, direct and motivate the followers of Christ to spread the Gospel;

- God’s purpose and plan to extend the Gospel – His plan of salvation – to Gentiles as well as Jews;

- God’s pattern for becoming a Christian – the fivefold elements (Acts 2:38-42)

- Repentance from sin;

- Water baptism;

- Receiving (and accepting) forgiveness for sin – past, present and future;

- Receiving the gift of the Holy Spirit – both indwelling and infilling;

- Becoming joined to and united with the body of Christ – the local family of God, the local Church;

“This pattern keeps reappearing in Acts, not always in the same sequence as in 2:38-42, but with the same elements present (e.g., 8:12-17; 10:44-48; 19:1-20)” (Walton, 2008 p. 80)

- The present reality of Old Testament promises. “Luke presents the church’s growth as fulfilling Scripture, with a particular stress on Isaiah and the Psalms (e.g., ‘fulfilment’ language is prominent in the key speech in 13:27, 29, 33-35, 41, citing Psalms, Isaiah, and Habakkuk)” (Walton, 2008 p. 76)

- The persecution that is the inevitable result of this expansion of the Kingdom of God into all corners of the earth (cf. Jesus’ “High Priestly prayer” in John 17);

- God’s provision to those undergoing persecution for His sake. His Father did not “take this cup” from Jesus, His unique Son (Lk. 22:42), but enabled Him to obey, even to death on the cross. So too we can expect God to enable us to persevere in the midst of our painful experiences, and thus be blessed (Mt. 5:10-12);

- Pastoral difficulties – people problems and problem people – Luke is above all honest in his portrayal of the growing pains of the early Church. Down through the centuries, the Church has always had to deal with people who just “don’t get it”. This is both an encouragement and a warning – when God moves, expect resistance from within and opposition from without – but don’t give up – keep believing in God and His power and purposes. Acts clearly shows that we, the Church, are an unstoppable force, because …;

- God’s people empowered by His Spirit are irresistible – God will conquer hearts and minds in and through His anointed people!

- God’s prescription (or model) for Church life, discipline and mission. If we learn to follow the original methods, albeit adapted for 21st century realities, we will bear much fruit, just as we were intended to from the beginning.

Historical Setting

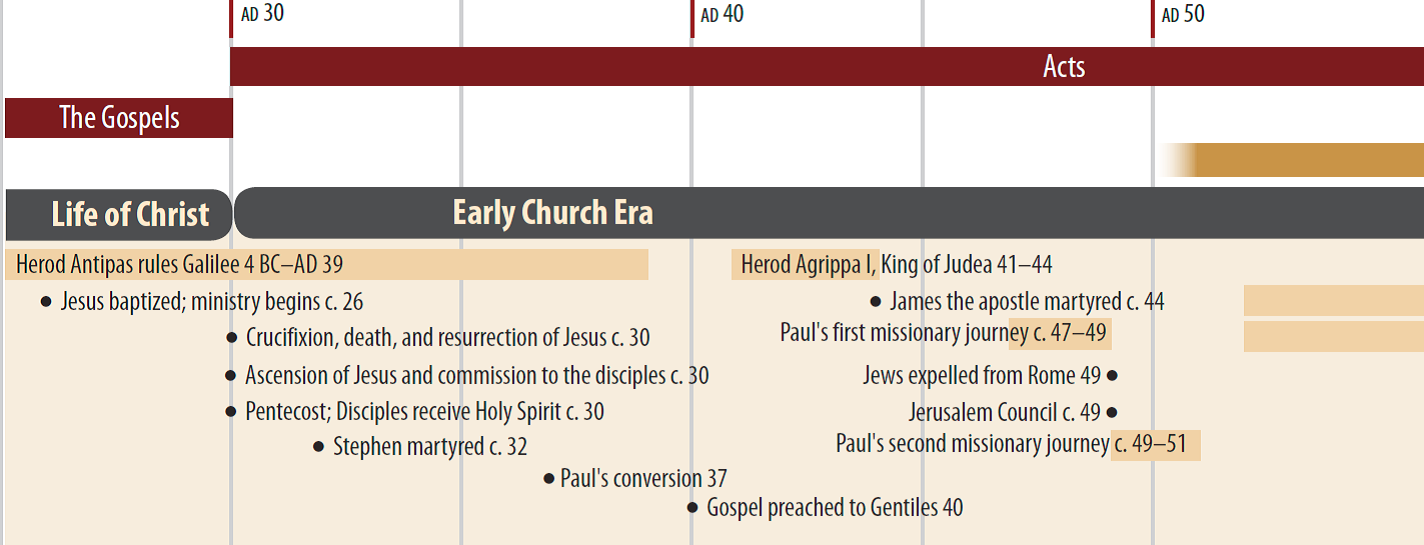

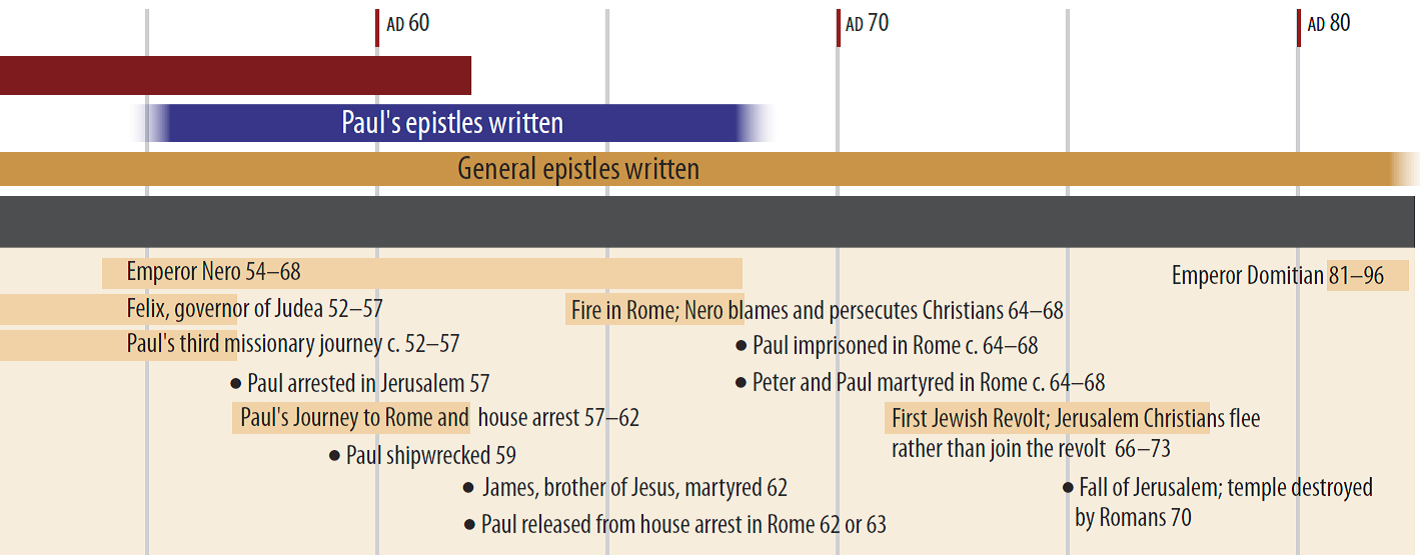

It can be helpful to see how the book of Acts aligns with events taking place elsewhere in the Roman Empire at the time. The following timeline diagram comes from (Galan, 2017 p. 188).

The Apostle Paul in Acts

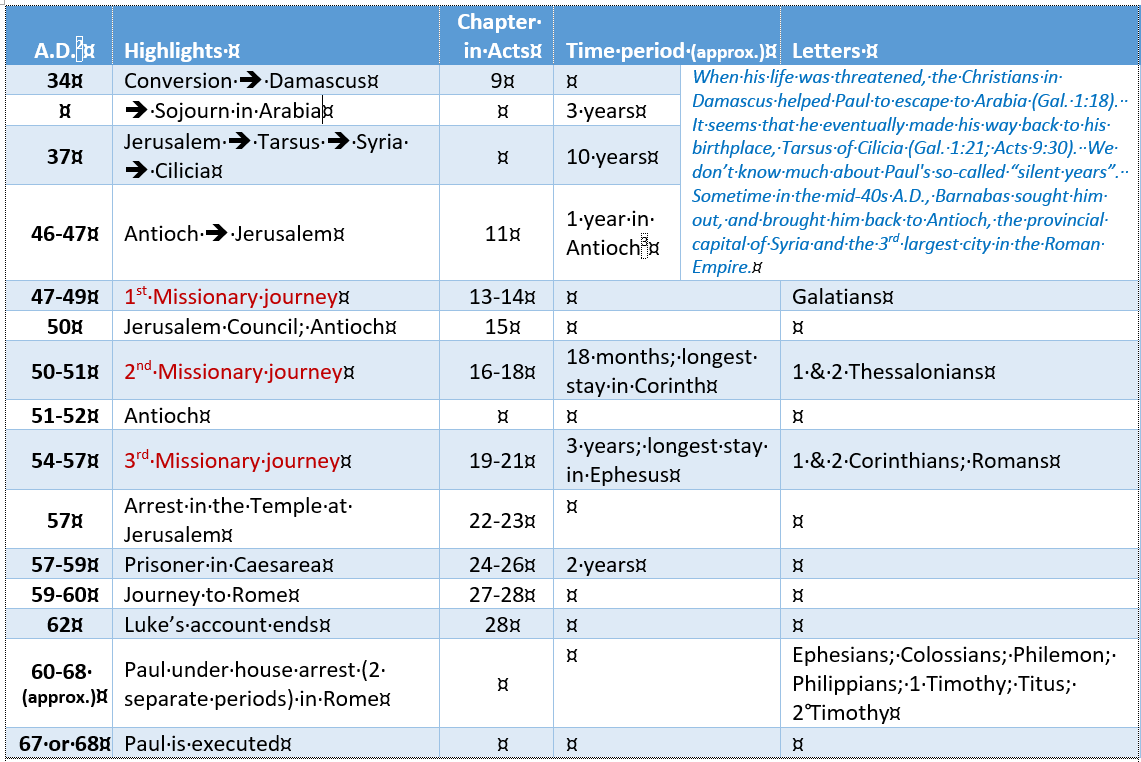

Arguably the 2nd most influential person1 in the whole of the New Testament is the man born Saul of Tarsus, who became the Apostle Paul. Saul was born in about 5 or 6 A.D. as a fully-fledged Roman citizen – a relatively rare status for that time – many had to purchase their citizenship or else remain non-citizens. We know relatively little about his early life apart from what he himself revealed. He tells us that he was educated “at the feet of Gamaliel” (22:3 lit. trans.), who was a highly respected teacher in Jerusalem between 22 and 55 A.D. He also tells us that he was proud to be a “Pharisee, the son of a Pharisee” (23:6), which meant that he adhered to the strictest interpretation of Jewish Law (26:5; Php. 3:5). We know that he was an extremist in his views, because of the way in which he attempted to stamp out those who began to turn away from Judaism and give their lives to following Jesus. However, as we know, Jesus had other plans for Paul, and he met him in the most powerful of ways as he journeyed to Damascus intent on rooting out more of the early Church.

The following table attempts to summarize the rest of Paul’s life and ministry, including some indication of when evangelical scholars believe that he wrote most of his letters to the churches that he founded.

Paul’s Missionary Journeys

Rather than reproduce annotated maps showing the route of Paul’s various journeys here, I’m going to direct you to an excellent website that displays them in animated form:

http://www.apostlepaulthefilm.com/paul/journeys.htm4

Conclusions

Acts is an extremely valuable, vibrant and vital sequel to Jesus’ ministry on earth. In fact can be viewed as His continuing Acts in and through His Spirit-anointed people, orchestrated from His position of supreme authority sat at the right hand of His Father in Heaven. Acts is a glorious story of the early Church and should be read and studied by all Christians in every age.

As we read this wonderful book, we should be asking the following questions of ourselves continually:

- How does our church experience match up to that of the early church? If there are marked differences, perhaps we need to re-evaluate and re-position ourselves to become more like them? Is God or man at the centre of our Church, and if it isn’t God, why not?

- Are we expecting God to move missionally within our locality and nation? Does prayer play a sufficiently large part in our walk with God? Are we open to hearing and obeying the voice of God in the way that we observe in the early church? What obstacles do we need to remove to enable Him to transform, direct and motivate us?

- Are we sufficiently evangelistic in our stance – both corporately and individually? If we learn nothing else from studying the book of Acts, we should learn to be willing at all times and in all places to present God’s plan of salvation to those around us (1 Pet. 3:15). We do well to remember and reflect upon the fact that during the first few centuries, believers were prepared to lay down their lives in order that some might hear and be saved.

References

Galan, Benjamin. 2017. Bible Overview. Torrance, CA : Rose Publishing, 2017. ISBN-13: 978-1596365698.

Walton, Steve. 2008. Acts. [book auth.] K. J., Treier, D., Wright, N. T. (Eds.) Vanhoozer. Theological Interpretation of the New Testament: A Book-by-Book Survey . Grand Rapids, MI : Baker Academic , 2008.

Footnotes

- Jesus (of course) was THE most influential person in the New Testament

- All dates are approximate. Some evangelical scholars place the dates at one or two years variance from the ones shown here.

- 3 + 10 + 1 equals the fourteen years that Paul mentions in Gal. 2:1, but the timings can only be approximate.

- Accessed on 28 Jul 2017

Gordon Smyrell (August 2017)